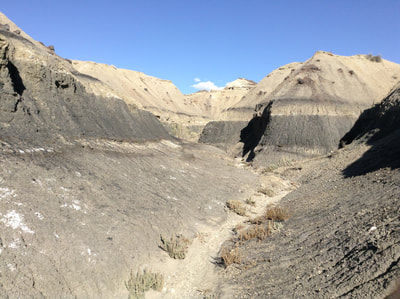

This bare landscape presents not a drop of available water, only a few patches of low brush, and tracks of rare wildlife passing through toward better places. A broad silt-gravel flat stretches between valley walls and rounded, isolated mounds of chalky shale. The mostly soft rock layers are gray, with accents of red, purple, and black. At certain levels on the valley the walls stand fields of hoodoos – clay pillars 2-3 feet high with overhanging sandstone caps.

Dimensions The flat is half a mile (1 km) wide, enclosed within 40 ft (12 m) high valley walls over a length of three miles (5 km). Isolated mounds are 5-40 ft (2-12 m) high, and tens to hundreds of feet (5-150 m) across.

Key Details

- Origin: Most of the ground here, ancient volcanic ash and shale, has been broken up and eroded away by impact of rain drops and sheets of running water during intense storms. Hoodoos are created where broken fragments of erosion-resistant sandstone literally act as umbrellas to shield the shale columns below.

- The thin black layers are coal. The darkest reds are natural ceramics – clays that were fired by coal deposits that burned long ago.

- Scattered across the flats are a few broken blocks and stumps of petrified wood, weathered out of the ash and coal. Loose dinosaur bones and teeth can also be found in this area.

- A narrow stream bed has cut down a few feet (1-2 m) into the broad valley flat, It is usually bone-dry, but runs occasionally with shallow flow fed by the more moderate rare storms. Fresh-looking ripple marks from those flows can last weeks after the bed again goes dry.

- The valley walls extend out irregularly onto the flat, with many large and small spurs and inlets. Anyone walking close to the walls will find more and more of the surrounding terrain blocked from view.

- Narrow slot-like ravines, cut into the valley sides, show the powerful erosive effects of intense rain runoff that sliced down through fractures in a thin sandstone cap and several feet/meters of soft shale. In places the walls of these clefts are so close, and the floors so irregular with fallen lumps of clay, that an explorer would need to squeeze and essentially climb horizontally, to penetrate further. The clay walls are crumbly, threatening further collapse. Many of these ravines end in small cave-like pipes extending several yards/meters into the shale, hollowed out by rainwater gushing from fractures.

- The caps of hoodoos are relatively solid plates of sandstone, limestone, or baked-clay ceramic. Most of the larger caps are stable to stand or sit on, but some have narrow enough clay columns below to give way, especially when the weight is placed off-center.

- Further upslope from the rims of valley walls, a sandstone layer becomes an unbroken shelf, the even base for a low forest of blocks on pillars, fragmented pieces of the next higher bed of stable rock. Ranks of hoodoos appear in this manner several times, until the ground ascends to the dry grassland that is the more typical face of the surrounding region.

Story Elements

- This desolate terrain evokes weird occurrences.

- People may come to this area to collect the unusual mineral and fossil deposits.

- This is a good setting for a stealthy tracking session or a wild, noisy pursuit. An approaching storm could provide a ticking clock. Seeking someone who has disappeared into this landscape, whether for rescue or capture, will involve uncomfortable climbs and descents, tedious walks across broad flats from one valley edge to another, and possibly ventures into tight crumbling places. Because of the difficulty surviving in this landscape, a need for haste may lead the pursuer to carelessness.

- During an intense storm, this normally quiet area will change. Raindrops and hailstones will bounce high off the bare ground, and portions of the ground surface will become slick sheets of mud, slowly flowing downhill. The narrow slot ravines and pipe caves at their heads will be especially dangerous places, with gushing water and collapsing walls.

- A character seeking shelter from an impending rainstorm/hailstorm might spy an unusually large hoodoo overhang, and witness the violent weather from beneath that ‘umbrella’.

- Wearing away of clay during a storm may uncover small pieces of dinosaur bones, which may collect in water flow paths.

- Because of the irregular spurs and deep inlets of the valley edges, a tricky climb up a well-placed clay dome or ridge may be needed to survey even adjacent low ground.

- To climb the valley walls, it is best to scale the relatively low-sloping, but still challenging, tips of the spurs. Ascending the crumbly, near-vertical walls within recesses of a slot ravine is impossible.

- It is easy to become lost in this terrain. Things that look like landmarks are much less distinctive when seen from another direction.

- Someone disoriented out on the open flat might happen on the dry stream bed, and get a clue to the right direction of escape by seeing some ripple marks there. These tiny mounds and ridges have steeper edges on the downstream side.

- Some portions of the valley walls are near-vertical, presenting no low-angle spurs to ease ascent. They do commonly have thin, hand-deep clefts etched into the shale by runnels of rainwater, which might provide some purchase for climbing. This type of obstacle might be presented as a challenge in foot-messenger skill training or a rite of passage.

- Nearby locals could have a custom of competitive balancing, racing or fighting on the caps of the hoodoos.

- Small creatures, sentries, cameras or other machines, could hide between/behind the hoodoos, or camouflage themselves as hoodoos.

Reference Location

Bisti Badlands Wilderness site, south of Farmington, northwestern New Mexico. This area has open public access via good quality gravel roads. Water must be carried in, and fossils should be left where they are found.

© Rice-Snows 2018

Proudly powered by Weebly