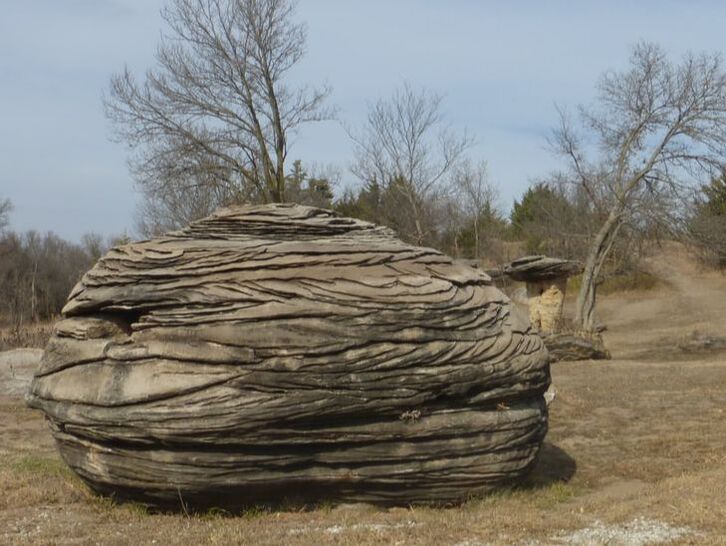

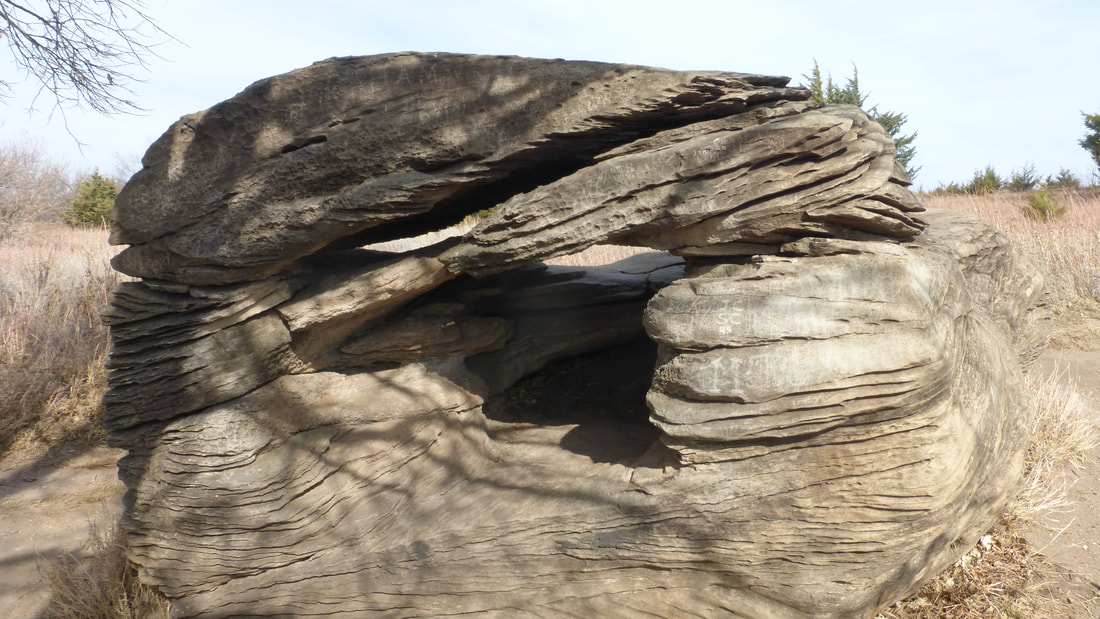

On rolling prairie, a cluster of giant, rounded stone pods is found among trees in a creek valley. Two of the massive gray forms stand elevated on narrow stalks of white sandstone, as if they have been placed on special display.

Dimensions The rounded rocks are 6-12 feet (2-4 meters) thick and 20-25 feet (7 meters) in diameter. Headroom is ample for anyone standing beneath the two elevated pods, which stand about a hundred yards (meters) apart.

Key Details

- Gentle rises and falls of the region's terrain hide these rock formations from ground-level view over much distance - a couple of hundred yards (meters) in almost any direction. Trees cluster only in low parts of the land, leaving 95% or more of the ground in grass open to the sky.

- All of the rock here is sandstone, despite having different hardness levels and appearance. It is lightly abrasive to the touch, and the surfaces of the dark gray pods are very hard. The sandstone of the light-colored pedestals below elevated pods is quite soft, easy to etch marks upon with a nail or knife.

- The elevated pods don't just rest on the pedestals below; they are firmly attached to them. However, like many such 'balanced rock' formations, one could still break free and come crashing down if enough weight or other force pushes on one of its outer edges.

- Origin: Sand was first laid down across the region by shifting rivers, then buried and compressed by the weight of further sediment layers. Small amounts of mineral deposits from groundwater cemented the sand grains together, but only slightly, forming a soft sandstone. A few layers and pod-shaped zones in the rock were cemented much more solidly by extra chemical deposits of calcium carbonate, the material that makes up limestone. The extra cement material in these spots may have been from broken-down shells buried in the sands. As rain and weathering in this dry environment finally wore down the region's bedrock, the more strongly cemented rock pods, called concretions, remained solid while the rain-weathered, lighter-colored rock around them disintegrated into loose sand. Most rock pods ended up simply resting on top of the sandy soil, but two effectively sheltered the weaker sandstone just below them, acting like rain umbrellas as many feet (several meters) of the surrounding ground was eroded away. These are now hoodoos, the hard pods held up by columns of the softer sandstone.

- The distinctive etched lines decorating the pods are due to cross-bedding within the sandstone, its small angled layers oriented in varying directions from ancient shifting water currents. This surface pattern is not evident on the light-colored, more roughly eroded rock of the hoodoo pedestals.

- Where weathering has wedged apart one of the stone pods lying on the ground, the pieces are wide, slightly curved plates weighing hundreds of pounds (kilograms). These rock sheets commonly rest at angles against boulders' sides, or between tree trunks.

- The soil here is very sandy, drying quickly after rain. In storms, the creek nearby rises and returns to normal levels more quickly than in regions with richer soil.

- While most pods have circular-outline shapes, oval in profile seen from the side, there is one more elongated rock mass shaped vaguely like a shoe. It is five yards/meters in length, with one rounded end and a higher, squared-off end that includes a short tunnel-like cavity large enough for a person to shelter in. Comfort inside is minimal, because the small opening at the other end admits the elements.

Story Elements

- The unusual rock formations make this an identifiable meeting point on the vastness of the prairie, although one not visible from great distance. It might be seen by many travelers as a landmark on an established trail, the creek serving a watering stop (possibly dry in some seasons, unless a well is in place). Nomads journeying cross-country could still encounter it by chance, or as they trace the creek valley.

- Locals might converge in this place for ceremonies or community gatherings. In the eyes of different beholders, the pods could be monumental effigies of bread loaves, lentils, turnips, stream pebbles, or cowpies. Bakers or cobblers might consider a pilgrimage here for increased skill/luck. Mushroom-like beings could see the hoodoos as great heroes turned to stone.

- Against the right level of overcast sky a viewer might miss the light-colored pedestal of a hoodoo, and puzzle at the dark saucer suspended above the ground.

- The soft sandstone pillar of a hoodoo base is a ready location to leave a scratched-in message in an easily described spot. There might be some confusion and delay in finding a message if the message-searchers pick the wrong hoodoo to begin with, unless directions are careful enough to note the differences in the shapes of the two hoodoos' pillars (one tapers up, the other down) and pods (one is rounder in profile, the other unusually rough and sharp-edged).

- Could some creatures that have shells be strangely drawn to these concretions, with the lingering essence of shell material now making up their cement? Imagine characters coming across these pedestal rocks, and finding a spiritual site of some shelled race.

- Characters could huddle under a hoodoo in a downpour, or flee there for more crucial protection in a hailstorm. They might need to move from one side of the pedestal to another with shifts in the wind.

- Where a loose sheet of rock from pod disintegration is leaning against something, it could be used for shelter or a hiding place. If characters can manage to move several of these slabs (hundreds of pounds each), they could build a more deliberately fortified spot among bracing trees and whole pods.

- The large pods lying on the ground are somewhat difficult to climb, because of their rounded profiles. The etched-out lines of the rock's cross-bedding can offer shallow finger-holds, to aid in the ascent. The top of one could be a vantage point to scan the horizon, or a place protected from melee fighters in combat.

- The top of a hoodoo could hold up to half a dozen people, maybe saving them from a stampede or pursuing predators. How to reach there, several yards/meters above ground level? Maybe a great feat of acrobatics, clever rope work, or use of a fallen tree trunk as a ladder? The group would be wise to cluster near the center of the pod top, because of the danger that someone might slip off a rounded edge, or that the group's weight might break free the pod and topple it.

Reference Location

Mushroom Rocks State Park, central Kansas. In this six-acre park, several concretion rock formations are within sight of the small parking/picnic area, and the rest are only a short walk away.

© Rice-Snows 2022

Proudly powered by Weebly