The ground surface in this chaotic landscape is a mixture of prairie and high mounds of soft shale bedrock. The flat bottomland runs right up to bare, steep clay walls that bow up toward the sky. The name ‘badland’ refers to the difficulty of travel across this area while keeping anything like consistent direction.

Dimensions Shale mounds are 15-30 feet (5-10 m) high. Mounds and the flat spaces between them are typically 20-60 feet (6-18 m) wide.

Key Details

- Origin: Badlands form where thick beds of shale are exposed at the ground surface. The clay making up these rocks does not allow rain to infiltrate into the ground, but is easy for trickles of surface runoff to sculpt, leaving deeply cut rills and a maze of small valleys and ridges. In this locale the erosion has removed much of the shale to allow a flat prairie surface to extend between isolated remnant mounds.

- Further off in one direction across this region there is a mostly unbroken plateau of shale capped with sandstone. In the opposite direction the shale mounds become sparser until the low prairie is uninterrupted, presenting long-distance vistas of sky and flat horizon.

- A small meandering river runs through this area, occasionally flooding all of the ground adjacent to the mounds for hours or days.

- The lower-level slopes of the shale mounds here are very steep and challenging to climb, but footing gets easier close to the mounds’ rounded crests.

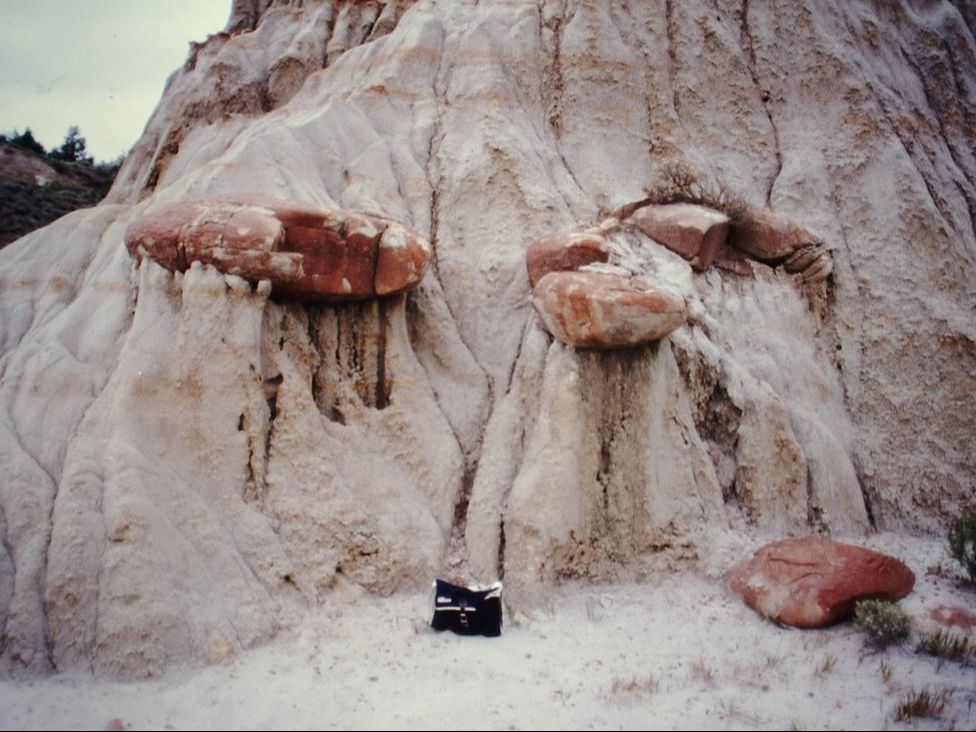

- Various thin horizontal layers of the shale have strongly contrasting colors: light and dark grays, browns, tans, and reds. At some levels on the sides of the mounds the striped effect is strong, accentuated by slight variations of slope angle that follow different layers. In lower portions of some slopes the color is more a homogeneous gray, with a vertical fluted texture of finely cut rills.

- Rounded lumps of harder rock stand out from the more easily eroded clay walls; some the size of messenger bags (see photo) and others as big as coffee tables. Their makeup varies from sandstone to the pure red-brown mineral siderite (iron carbonate). Iron staining trails down onto the shale slopes from many of these nodules. A number of these can be found completely detached, fallen on the ground at slope bases. Others look weirdly suspended, extending out far from the shale surface but still firmly rooted.

- The northern sides of many mounds are less steep, covered with juniper bushes. The soil is somewhat moister here, with less heat from the sun, so that vegetation can grow and keep more of the soil in place.

- While yearly precipitation is low, rain usually comes in heavy downpours. In these events, whole portions of slopes occasionally slough off to the ground in small landslides. Slope surfaces can be slick following rainfall.

- Turf and low brush on the flats are grazed by mule deer and herds of bison. Rattlesnakes feed on prairie dogs that build their own low mounds on the prairie surface.

- At bases of the mounds the abrupt change from steep slope to absolutely flat ground is striking, more reminiscent of a large tree base rising from the ground than a hill. This weirdly severe boundary may be partly an effect of lapping flood waters or trampling of all available low ground by bison herds.

Story Elements

- Visibility is severely limited at ground level. Climbing a shale mound provides a vantage point over an immediate surrounding area (except possibly the ground right at the base of that mound). Still, other mounds block sight of many possible approaches from distance.

- This could be a meeting location for groups from the plateau and lower prairie flat lands to either side of this rough boundary area.

- This badlands area extends miles away from the river, and the more distant areas lack ready sources of water. Finding the river hidden by the closely spaced mounds might be a day's challenge for those not familiar with the area.

- Climbing the exposed shale sides of the mounds is very difficult in most spots. Metal tools like sturdy knives or climbing picks would help, so long as the clay surface is not slippery from recent rain.

- The lower-sloped northern sides of the mounds allow easier ascent, although the common dense cover of low juniper trees trees and scratchy juniper bushes makes some obstacle. It is possible to clamber over the tops of bushes, taking care to find hand- and footholds on thicker branches and bowed trunks. Blundering through the juniper without complete skin protection will result in abrasions, possibly with an allergic reaction and rash to follow.

- The crests of many mounds are quite small in area, with near-level space for only one or two people. Other, more steep ground near the crests will be uncomfortable to rest on, and fairly treacherous to move about on.

- Navigating in the badlands to travel in an intended direction will be considerably easier with compass or a visible sun or moon in the sky. A weather change to overcast sky or swirling snow could be very bad news.

- A person trying to escape rising floodwaters or a moving bison herd might try climbing up onto one of the protruding nodules on a mound wall, a few feet above ground level. It is likely to firmly support the extra weight, but if nearly eroded free it may collapse immediately (or more slowly sag if the clay is wet).

- Where folds in the slopes gather rain water running down from above, low fan-shaped sheets of silt and sand have formed at base of the slope, burying the grass. These bare patches may be good locations to spot recently-left tracks or find partly buried small objects dropped before the last cloudburst.

- Siderite found in the nodules is about fifty per cent iron, and useful iron ore. Carting away one of the larger nodules would keep an iron-age backyard smelting operation going for weeks, and siderite is a valued component for some more sophisticated blast furnace steelmaking. The resource here is limited - gathering and shallow mining by a large group would quickly exhaust it.

- The mounds call to mind a giant group of huts. A hermit's home could in fact be tunneled into one of the mounds, or a village into many, so long as the hollowed-out spaces were above flood level. Some interesting architectural elements might result from the weakness of the wall/ceiling material, possibly requiring interior spaces to remain narrow with peaked ceilings, and thick exterior walls to provide support and allow for chance sloughing off of the exterior surface.

- Low-angle sunlight will accentuate the richly colored level banding of the shale mounds, and will also cast starkly contrasting areas of brightness and shadow on the mound walls and prairie surface.

- Because of the domed form of the mounds, a person keeping close to the base of a mound will be hidden from, but will also not be able to observe, someone on the mound crest. However the shadow of the person on mound crest may be cast on the prairie floor below or on the bare wall of a nearby mound, alerting the one at the mound base to their presence or movements.

Reference Location

Theodore Roosevelt National Park (South Unit), southwestern North Dakota.

© Rice-Snows 2017

Proudly powered by Weebly