This narrow valley is enclosed by vertical cliffs of salmon-colored sandstone. Its central floor also shows the same tan-red hue on a broad, clean, flat surface of the stone, stepping down gradually along the valley length. Irregular slopes of poor sandy soil, brush, and rounded sandstone overhangs flank the canyon floor, rising toward bases of the stone walls.

Dimensions The canyon walls are separated by about 500 ft (150 m), while the clean valley floor width is 100 ft (30 m). The valley floor drops 350 ft (100 m) over its mile (1.6 km) length, and the surrounding cliffs rise 100-250 ft (30-75 m).

Key Details

- The vertical rock face enclosing one side of the canyon is a true wall: a tall fin of sandstone only 30-150 feet (10-50 m) thick, just as steep on its other side. These rock fins are a common feature in this area, remnants from weathering and erosion cutting along parallel vertical fractures (joints) in the bedrock, leaving only a few solid rock masses between fractures still standing high. Beyond the long rock wall on the side of this canyon is a much wider valley area with more scattered rock fins.

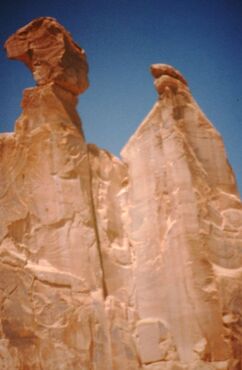

- The cliff on the other side of the canyon fronts a broad sandstone upland that steps up even higher and is capped by rock spires and fin fragments, several of which are memorably human-shaped rock formations visible from parts of the canyon floor.

- When this parched environment is subjected to a cloudburst, maybe once or twice a year, it becomes clear that the flat valley floor is a sort of stream bed. A sheet of moving water, likely ankle- or shin-deep, covers the whole surface, sweeping away any loose sand and plant debris.

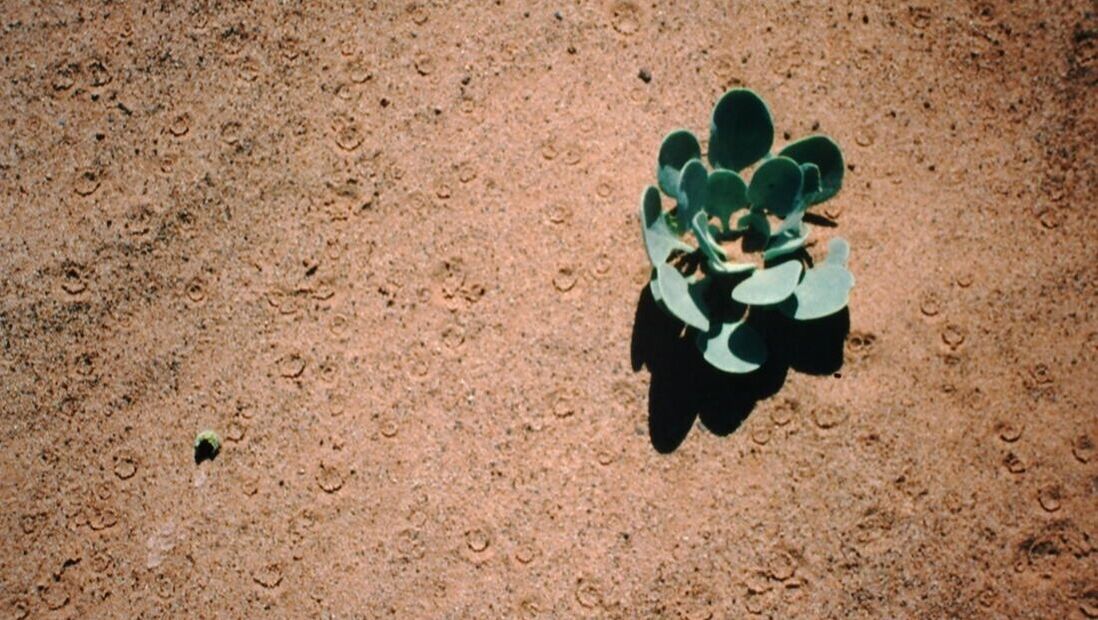

- In rare spots on the valley floor, the sandstone flat is cut by a line of erosion pits or a narrow, sinuous cleft resulting from water erosion of the rock surface. Why was the broad water flow able to etch the rock in these places, but not everywhere else? Some of these marks, but not all, seem to follow subtle cracks in the stone. Maybe these are places where flow directions converge in the short-lived sheets of storm water, creating turbulence and gaining erosive energy.

- The clean sandstone surface provides plenty of traction for running on the flat ground or climbing on a low-angled slope, but a scattering of loose sand grains can make it much easier to slip.

- At noontime there is almost no shade to be found within the canyon, with the only pools of shadow being below slightly overhanging rock ledges adjoining the valley flat. There are are very few of these spots, and each shade patch is only able to shelter one or two persons.

- Ravens are the largest commonly seen birds here, croaking and flitting between the ground and high perches.

- There are interesting detail features to be found on the ground here. Fine bands of layering are clear to see in the sandstone, worked into curving patterns by weathering of the surface. In some spots these stripes are made jagged by ancient, tiny fracture-line slips in the sand deposits that became stone. On part of the valley side exposing loose sand to view, tiny discs made up of sand grains, dry but still holding together, mark the imprints of raindrops from a recent brief shower.

Story Elements

- This is an apt physical setting for a story in which characters feel confined to a single path of action, with no real choice but to keep going or go back.

- A disoriented person on the canyon floor could finally realize their location and the best way out of the canyon by sighting one of the distinctive rock formations on the cliff crest, or its shadow on the opposite canyon wall.

- In a dream, the giant anthropomorphic stone figures might come to life, descend into the canyon, and council the dreamer.

- A raven, inching closer on the ground, speaks a few clearly recognizable human words.

- A group of travelers in height of summer, each one taking any available shade spot over a noon rest break, might end up scattered along hundreds of yards the valley floor. They could still have 'conversation' by relayed shouting or exchanged song up and down the canyon.

- On one side of the normally clean, flat canyon floor, a broad spray of sand and soil clumps might be a clue of a recent violent altercation higher up on the valley side, or a group of people that climbed up off the canyon floor here, to hide within the patches of brush above.

- Someone might need to make a perilous walk across the canyon floor through shin-deep storm runoff. They would be able to keep their footing so long as the floor stays flat, but would likely stumble if encountering the deeper, more turbulent water over a rock surface erosion pit or cleft, and be carried away some distance down the valley. If recognized, such a dangerous footing zone might require a longer diversion of path through the shallow flow.

- As a rainfall flood abates, the sheet of water may be only an inch (2 cm) deep and moving slowly, but water collected into a cleft would still be racing along, capable of carrying a small object away quite a distance down the canyon before it comes to rest. The brief, stronger water flow during a cloudburst might leave something larger (a satchel? a body?) wedged into an erosion cleft.

- Local people, seeking water wherever possible, might construct a low dam across the canyon floor, ready to retain a broad pool of water from each cloudburst. The water could take several days to fully soak down into the porous sandstone. In the meantime, the community might call a holiday and enjoy the chance to gather and luxuriate in the novelty of a wide pond of clear, fresh water. Entirely different set of social practices might be in effect in this special, unpredictable time.

Reference Location

Park Avenue hiking trail, Arches National Park, Utah. There are trail heads and small parking areas at both ends of the canyon, in this area fairly close to the park entrance.

© Rice-Snows 2019

Proudly powered by Weebly