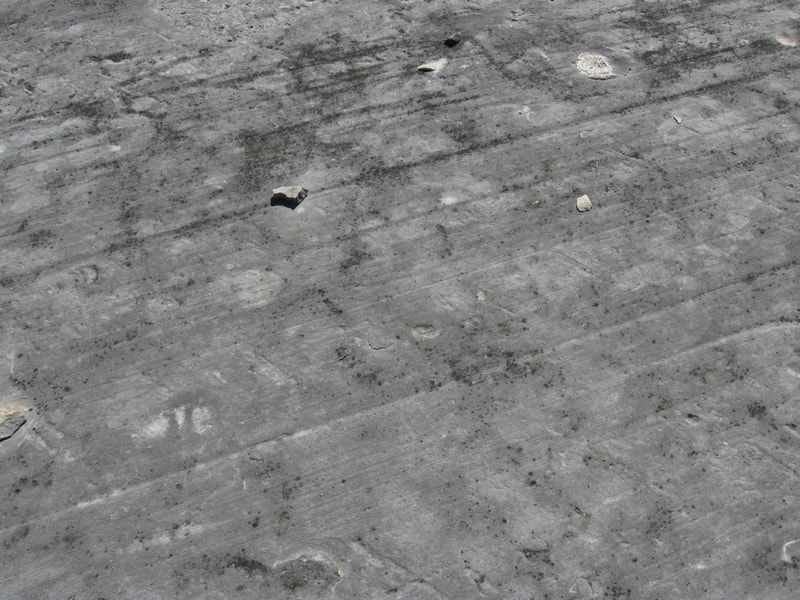

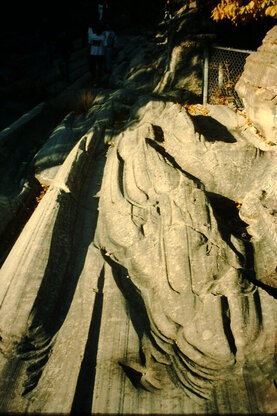

A vast, cleared area of bare bedrock interrupts the woodlands. Much of this limestone surface is perfectly flat, with thousands of long scratches running in exact parallel, east to west. Elsewhere the bedrock surface is rougher, and trees take root in small islands of soil. A few long, deep trenches interrupt the level surface. These giant grooves run in the same direction the scratches do, but are 10 feet (3 m) deep and 30 feet (10 m) wide. Their interior surfaces are sculpted into smaller, foot-deep grooves, ridges and mounds of bedrock, all etched with crescent-shaped gouges and parallel scratches. Upper rims of the giant grooves are sharp, and the contrast between simplicity of flat table-land and complexity of deeply-cut grooves is striking.

Dimensions The bare limestone surface is 2000 feet (600 m) across. Grooves run hundreds of feet (more than 100 meters), east-west. The grooves have very uneven spacing, north-south, so that the width of flat rock surface between two such trenches may be tens of feet, or hundreds (approx. 10-100 m).

Key Details

- The broad, gray limestone surface is interrupted by quite linear, parallel fractures spaced widely apart (tens of yards/meters). Grass and shrubs have taken root in these vertical cracks over much of their lengths, as well as in a few scattered islands of thin soil, giving some slight barrier to view and movement over the otherwise featureless rock plain.

- Most of the scratches on the rock surface are so fine that it takes some attention to notice them by touch alone, though they give a strong visual impression . Some wider marks may be a millimeter or two deep, felt as a difference in roughness when brushing a hand one direction over the surface, and then another.

- This area of limestone bedrock was cut flat by the continental ice sheet that covered it in the past. Edges of stones and boulders held fast in the ice of the glacier's sliding base were the tools that scoured and scratched the surface to a near-perfect level form.

- Most of the deeply cut troughs are near-linear in gross shape, though not as exactly straight and parallel as the fine glacial scratches on the rock flat. Rare examples of these giant grooves have significant bends, meandering shapes, and branched ends, while staying overall in east-west alignment.

|

- Because the giant grooves mostly run almost directly east to west, in clear weather the south interior wall of a giant groove is in shadow through most of the day, while sunlight accentuates details of rock surface form on the north wall. At equinox, light from sunrise and sunset shines straight down the giant grooves’ lengths.

- This limestone is full of fossils, masses of coral and remains of other marine organisms. These show up on the smooth surface in cross-section, as if cut with a saw. We are seeing a literal slice of life on a shallow-water reef in a sea hundreds of millions of years old.

- In autumn the surrounding deciduous forest supplies large numbers of fallen leaves. When dried, these blow great distances over the bare rock flat. They collect as drifts on the floors of the giant grooves, elevating briefly again into clouds as wind gusts pass up and down the trenches' lengths.

- The smooth but strongly undulating rock surface within a giant groove makes for difficult footing (the scratches are too fine to produce much traction). Through most of the year, smaller depressions on the groove floors are filled with stagnant, pooled rainwater and decaying leaves. The giant groove floors do slope along their lengths, reaching to the edge of the rock flat, so the whole floors of these huge natural gutters never become large ponds.

- At midday in hot summer weather, the bare, reflective rock surfaces make this area feel a bit like a solar oven.

Story Elements

- This site can host an enormous group gathering, or even an evening dance (the flatter parts of the rock surface are almost as smooth and level as a ballroom floor).

- In fog or darkness, a wise character could keep properly oriented by the direction of scratches on the rock surface, viewing them with flashlight or carefully sensing them by touch. (This would not stop a really disoriented character from going in exactly the opposite direction than intended.) If already acquainted with the site’s general layout, the character would know that following the direction of scratches would be the most likely path to avoid meeting the edge of a groove, and that running across the direction of scratches would increase the chance finding a groove.

- Characters might escape sun glare and heat in shadowed parts of the grooves.

- Within a groove a character will have long views down the near-straight depression’s length, but no sight of the higher, flat ground surface to either side.

- How would it feel to be in one of the giant grooves . . .

- while it was still beneath the glacier, just after a basal flood had dissipated, leaving a dark air-filled cavity with an ice roof slowly bulging down, likely to completely re-fill the empty space in a matter of days?

- on a frigid, sunny winter day, when blowing tendrils of snow moving along the flat rock surface make a bright, filmy roof over the space in the trench?

- in the late fall, when a change of wind fills the air with a cloud of twisting dry leaves?

- early or late in the day at solstice, when your long shadow runs in exact parallel with the small grooves?

- in intense rainfall, when running water and over-brimming ponds fill every depression of the rock surface, and rivulets of water wash down from the rock flat above?

- in thick fog, whispering to barely visible allies also hiding in the trench, listening for approaching footsteps on the rock surface above?

- A race along the grooves would be a lark in relaxed circumstances, but brutal if consequences are dire. A race course north-south across the rock surface would briefly be an obstacle course (or jump challenge) where crossing a giant groove.

- Tiny characters would find the groove interiors to be even more challenging terrain.

- A memorable fossil exposed in the rock surface could be used as a clue to a key hiding/meeting spot.

- Is some intentionally sculpted symbol obscured among the streamlined bedrock forms of a groove floor?

- In a blizzard, powdery wind-blown snow lying only inches deep on the flat rock surface might give way to a hidden snow-filled giant groove that could swallow someone up completely.

- A home or fortress might be sited here to take advantage of the flat rock surface, and possibly the barriers made by grooves.

- On a large groove’s floor, a camouflaged creature might conform to a small groove, or imitate a rock ridge.

- Combat Dynamics:

- There is generally nowhere to hide on open parts of the table-land, other than by dropping into a groove or crouching in a thin hedge of shrubs rooted in a fracture line.

- Tricky footing on groove floors and fall hazards at edges of grooves will hamper close combat. There will likely be odd moments in progress of a fight, such as opponents reversing relative heights from moment to moment, or a deep, splashing step into what looked like a shallow drift of dry leaves.

- ‘Trench warfare’ tactics are likely to prevail in a large battle here.

Reference Location

Glacial Grooves State Memorial, Kelleys Island, Ohio. This single giant groove is all that remains of a broad surface containing several grooves, removed by quarrying in the 19th and 20th Centuries. Public viewing is from behind a low fence and on elevated walkway. A glacially flattened area of rock surface survives on private quarry land, five miles to the south near the east end of the Marblehead Peninsula. Other scenes within a few miles/kilometers of distance are Flatrock Point and Crystal Chamber.

© Rice-Snows 2019

Proudly powered by Weebly